Feature image by Rebecca Barrett

By Erin Davidson

@erin.e.davidson

Recently, I have become aware of how my self-proclaimed “body positivity” was built on the fragile foundation of other people’s opinions.

I used to think that because I did not hate my body most days or meet the diagnostic criteria for an eating disorder, that I had this whole body-love thing figured out. It was easy, I thought, a simple formula of eating what you want, exercising in a way that is fun, and not worrying about how you look. I observed women I admired criticizing their bodies and I got angry. How could some of the most amazing women I know still be limited by what they looked like? I mean, Oprah has body issues. Oprah!

What I was missing was the realization that I was ticking a whole lot of the privilege boxes. A combination of genetics, lifestyle (working as a fitness instructor), and youthful metabolism that squeezed me into how society defines an “acceptable” body. So, as it often does, it took drifting outside of the privilege bubble to realize exactly what I had been benefiting from.

At the same time, as we all know, women are put under immense pressure to fit into a narrow aesthetic ideal. Fitting into society’s expectations does not protect against body image issues or disordered eating. Many a time I have done the post-shower-stand-off, swaying my triceps or fanning my fingertips over my cellulite in the mirror. The searing pain that occurs when you feel let down by the figure standing in front of you.

In fact, I think I found this feeling too painful.

I grew up with a gorgeous, Jane-Fonda-level fit mother, who never seemed to see herself as such. I wondered: If she couldn’t see herself as beautiful, then how could I? I witnessed her struggle and refused to let that also be my own.

In an act of unconscious rebellion, I actively repressed my own body criticisms and insecurities. While the result of this may seem positive, it’s actually quite different than cultivating an intrinsic sense of self-worth.

As humans, we strive to feel good about ourselves. If that core positive sense of self is missing, our minds naturally latch on to external sources of validation. This could be anything from compliments, to “likes,” to party invites, to job opportunities.

I would keep a mental list of examples for when other people thought that I was good enough, rather than finding that sense of self-worth within.

The thing about this self-esteem strategy is that when you are getting good reviews, there is no better feeling; it is a confidence sugar high. It is a strategy based on comparison. It is a sense of feeling “better than” or “worse than” others. It’s the experience we frequently have when scrolling past Instagram models, watching one of those Netflix shows where all of the actors are unreasonably hot (*cough* Riverdale), or even looking at our own 2010 Spring Break photos.

And it should be noted that this approach to building self-worth is also not limited to appearance. Take academics, for example, when we feel better or worse about our grades depending on what the class average is.

This “strategy” is not without its risks. External validation is a high from an unreliable dealer. We cannot control what other people think of us. What happens when the feedback is not good? For me, my body, and other people’s approval of it became a large part of how I understood myself. Any whiff of disapproval added up to an identity crisis.

Over the past few months I have been slow-fading out of teaching fitness classes and moving towards my dream of becoming a psychotherapist. The shift from spending most of the day sitting on my butt, instead of a stationary bike blasting Nicki Minaj has naturally led to changes in my body. As my physique softens, it has unearthed a self-consciousness I was previously blind to.

Last summer, I had an experience at the fitness studio I worked at that slapped the Kool-Aid cup of body-positivity right out of my hand. The studio was doing a photo-shoot for social media promos. In the past I had received an invite to such a thing. This time, however, I learned that I had not been asked to join for the photos happening with a small selection of the instructors. I remember learning of this as I was closing up after teaching a class. One of the instructors was touching up her makeup and asked if I was coming to the shoot downtown. In that moment, my brain crowded with thoughts of not being thin enough, toned enough, attractive enough, or young enough. I felt cloaked in a weighted blanket of shame. I faked indifference and a smile as I let her know that I would not be attending. I then felt embarrassed for having all of these not-enough feelings about my body. This single instance of not receiving (what I perceived to be) external validation of my attractiveness was enough to unravel my entire sense of self-worth. I felt the intense contradiction of my body positivity and my feeling like a bag of shit.

My former strategy in a moment of low self-esteem, such as this, would be to do some mental math to cancel out the negative thoughts towards myself.For example, I may recall a compliment I had received earlier that day, an unrelated past achievement, or I would think about how the photo-shoot decision was likely not personal. All of these thoughts may bring some comfort, but they are a Band-Aid to a wound that required stitches.

This experience awakened me to the extent that I was building my sense of self-worth by comparing myself to others. I have started practicing what I preach as a therapist by turning to the concept of self-compassion to provide me with a new map to navigate my self-criticisms. I learned that the alternative to a comparative method of self-esteem comes out of a habit of relating to yourself in a kinder way: replacing self-comparison, with self-compassion.

What does this actually look like?

1. Acknowledge that this shit is hard. Understand that you live in a society that implicitly and explicitly teaches that your value is based on your appearance. You are fighting a war to feel good about yourself. It is natural to have days where your appearance impacts your self-esteem, both positively and negatively.

2. Say “Hi” to your inner critic. Know that, as we all do, you have an inner critic that is worried and trying to protect you from pain. While it is well intentioned, your inner critic uses harsh language that typically works to sabotage and cut you down. When critical thoughts arise— rather than deny or judge them— say “Hello.” Show your critic some empathy; say gently, “I hear you are worried. I have this covered. I don’t need you right now.”

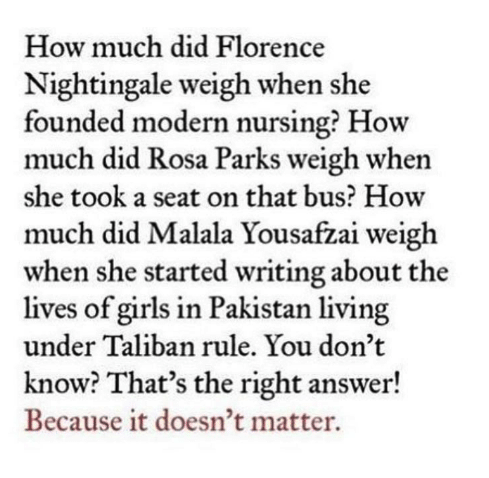

3. Pretend it doesn’t matter. Because it truly does not. Your appearance does not control whether you will accomplish your goals or find love. If it does, that is not the job or the person for you. Every time a critical thought arises, ask yourself, “What if this does not matter?” For example, if you look in the mirror and see that you have some extra weight on your tummy that you might not be happy about, ask “What if it does not matter that I do not have a six pack?” Experiment by trying this technique on for fifteen minutes, a day, a week, or a month.

In my life, self-compassion is a choice and a practice. Since it was my norm for many years, self-comparison is still my default setting; and my self-comparison muscles are not ready to give up without a fight. There are moments where I struggle, and I have to make a conscious choice to be kind rather than comparative or critical. I have decided that my work, my self-expression, my health, and my loved ones are infinitely more deserving of my time and energy. I am committed to choosing a life where my worth is not dictated by other people’s approval of my body. I am choosing to step off the self-esteem rollercoaster.

At its core, self-compassion is about embracing your own humanity. Nothing is wrong with you if you have cellulite, ingrown hairs, pimples, or stretch marks. In fact, it is human to have these things. The absence of flaws does not make you better than anyone else. Your imperfections make you real, multifaceted, and beautiful. We are taught that to be a person of worth, we must be better than others (or measure up to unrealistic beauty standards), when to be worthy of compassion and love, we just need to exist on this planet.

Erin is in the final stretch of her master’s degree to become a therapist and currently works as a counsellor at a women’s health clinic. Her hobbies include: crossing the street to avoid small talk, eavesdropping on bus conversations, and crying at work. Read read more of Erin’s work on erineileen.com