By Andrea Loewen

@ms.andreajoy

Can a board game be an act of resistance?

You may have spent your childhood playing Snakes and Ladders in your cousin’s basement, but the game dates back much farther than you might realize: originally called Moksha Patam, it began as a tool to teach morality to children in India in the second century.

After British colonizers took the game, stripped away the moral lessons, and brightened up the colour scheme, it became yet another example of cultural appropriation, complete with pictures of blonde girls in pigtails on the cover.

Now, it’s been transformed again, this time as a tool to fight neocolonialism, thanks to North Vancouver-based Squamish artist and educator Ta7talíya Michelle Nahanee.

“The board game is a rhetorical tool to increase acceptance of difficult decolonial ways of seeing,” explains Nahanee. “It communicates the opportunity for a do-over, it creates a container to put the concepts and it illustrates the time and space we are in as messy and full of mistakes that need to be talked through.”

The game takes its form from the familiar structure of snakes and ladders, but she replaced the snake with Sínhulkay, the double-headed serpent of Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish) stories.

“In my work [Sínhulkay] represents the two-faces of neocolonialism,” says Nahanee. “Things that look like helping but are harmful. The most clear example of this is the Indian Residential School system and its ongoing impacts. It was framed and funded as helping while it was clearly incredibly harmful. In my game, I shared this help/harm axis as a decolonizing practices framework to analyse any situation for neocolonial bias.”

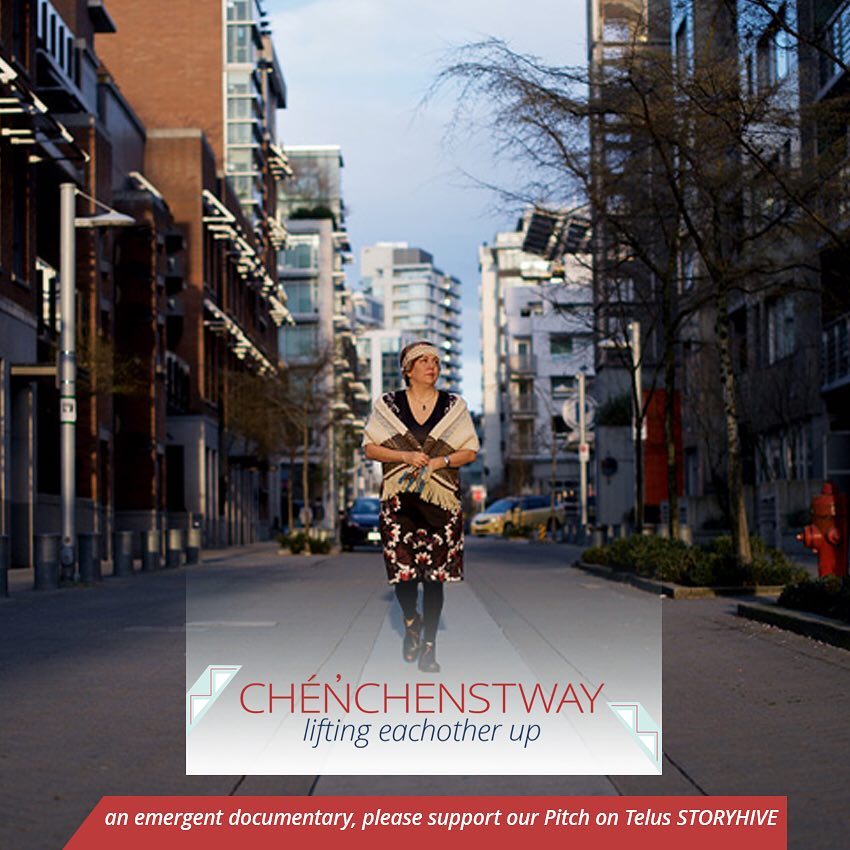

The other vital aspect of the game is Chénchenstway, the Squamish verb for upholding one another.

“It is one of our sacred laws, which I share as another decolonizing practices framework to analyse any situation and ask if we are truly holding each other up. Is this reciprocal? In colonialism, one is always benefiting while the other is not. But, what if we applied Indigenous law to our relations? That is one of the questions I am asking,” explains Nahanee.

These questions began for Nahanee after she completed her master’s degree, which she says she could have titled: What I wish I knew in my twenties.

“Through my research I finally understood the encumbrances of colonial impacts on my life and the links to invisible power structures we are all living in,” she says. “But, I didn’t make it to grade 12. I spent my youth years in trauma, disconnection and foster-care, and I didn’t know these were connected to colonialism. Like many Indigenous people, I thought my situation was my fault. Sharing my unlearning of colonialism has become my focus. Excitement about what happens when we all share reciprocally has become my driver.”

This game is played through small workshops, generally in corporate settings. In many ways it’s a picture of small acts of resistance: no global movements, no giant lawsuits or protests, just group training sessions where each player begins by recognizing that colonialism is a present problem and that they want to embrace discomfort and learn how to do something about it.

“I love witnessing the transformation,” says Nahanee on the impact of the workshop. “From a participant sharing ‘I’ve never accepted the word unceded but now I get it’ to organizers telling me the workshop was ‘truly transformational.’ At the end of every workshop, participants write a giveaway (something they commit to) and a takeway (something they learned or unlearned). I design posters of their writing and [take] a photo of the group so they can inspire each other anonymously. I’ve been told that groups continue to reference the poster as a check-in moving forward.”

I had the chance to play the game through a session organized by the North Shore Immigrant Inclusion Partnership. Played on a large “board” (think a life-size mat such as Twister), the players must actively participate: we are the pieces that move across the board. Squares include positive, helpful acts towards decolonizing; the ladders, while the pitfalls, or sínhulkay, are acts that may have begun with good intentions but ended poorly.

After an introduction where each player must recognize that colonialism is present in our society, that it’s a problem, and that we wanted to help fix it, we began rolling the dice to play.

The result? One of the most fun and active conversations I have ever had about what it might mean to decolonize.

If you would like to try playing Sínhulkay and Ladders yourself, you can book a session through Nahanee’s website, Decolonizing Practices. Follow her on Instagram for updates.