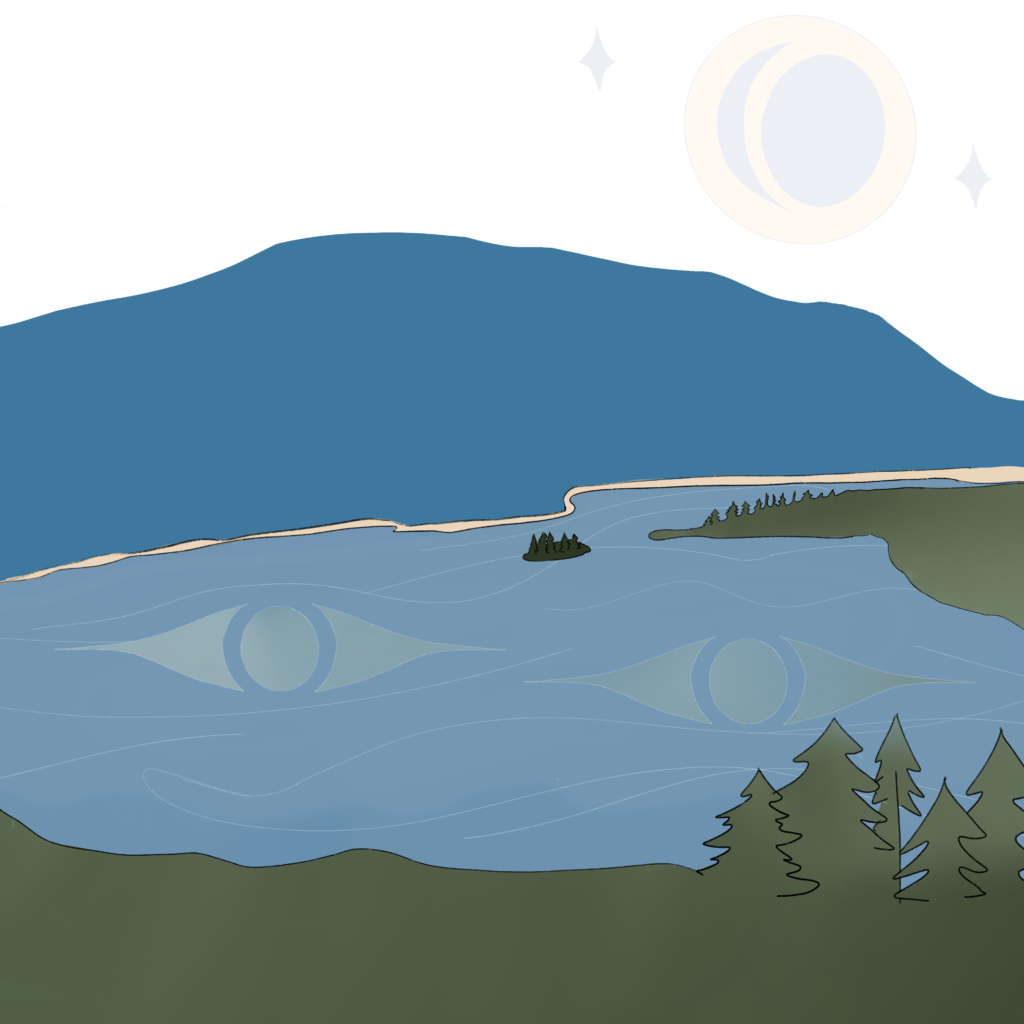

(səlil̓ilw̓ətaʔɬ)

Cultural Advising by Nikki Sanchez-Hood, Decolonize Together

Kayah George (she/they) is many things. A water protector, a gender-fluid carrier of creation stories, and matriarch-in-training who rests comfortably between her two Coast Salish identities: the Tsleil-Waututh Nation and Tulalip Tribes. Born on Tulalip territory — colonially known as Everett, Washington — George proudly carries the teachings of her mixed Coast Salish identities.

It’s through these teachings that George (whose ancestral name is ‘Halth-Leah’) has become a voice for the voiceless, such as the Orca Whales that swim the inlet sacred to the Tsleil-Waututh, and a keeper of some of the nation’s creation stories.

In your own words, who are the Tsleil-Waututh people and what do you want settlers to know about them?

Tsleil-Waututh directly translates to “people of the inlet,” and I think it’s really important to know that people along the coast, their identity is very much tied to the land and to the water. Tulalip means “little mouth bay.” So, a lot of these names of places are directly related and tied to the water. This is who we are — a part of the land. It will always be sacred.

The water is our oldest grandmother, the Burrard Inlet is the first grandmother of the Tsleil-Waututh people. People see [the land and water] as something to exploit and they see it for its extrinsic value instead of its intrinsic value, instead of something that is very sacred and beautiful, and it takes care of us.

We were taught that when the tide is out, the table is set and that the water, she’s taken care of us since the beginning of time, and we must turn around and take care of her in return and preserve her beauty, preserve her life, preserve her spirit.

I read that you carry the teachings of both the Tulalip and Tsleil-Waututh Nations. Can you tell me what each of these nations mean to you in terms of matriarchy?

Matriarchy is huge. Both cultures are matriarchal cultures. Tulalip in Washington is a Coast Salish nation as well, and so we know a lot of the teachings are passed down through the grandmothers and they have a lot of final say. The matriarch is the oldest grandmother in the nation, and for a long time, there was definitely a colonized influence of patriarchy, but as we’ve returned to our culture and our ways of being, we’ve found that in Tsleil-Waututh Nation, they’ve had majority female council members. As we reclaim our culture and connect with our land, that seems to happen naturally.

How do you feel about the term “Coast Salish” in relation to your nation(s)?

I think Coast Salish is an appropriate term, but if you want to be more respectful, you should refer to the actual name of the nation. Coast Salish is a blanket term, but it unites us, and so that’s why it’s appropriate. From southern Oregon to mid-BC, that’s Coastal Salish territory. A lot of us are longhouse cultures and we have similar languages and houses and canoes, so it fits. It unites us, but it’s more appropriate to reference the exact name and exact territory when possible.

Tell me about your involvement in the Sacred Trust Initiative.

Tsleil-Waututh Sacred Trust is what I refer people most to when they want to learn more about the inlet and more about the people and more about our sacred laws. Sacred Trust was created in response to development that’s happened. It’s our sacred duty in our laws and our culture that leads us to protecting our land and our water, and when we make decisions. Tsleil-Waututh likes to say, ‘We’re not anti-industry, necessarily, we’re not anti-development, only in the times where it affects future generations negatively and affects our land negatively.’ We’re really open to business and open to creating prosperity for our nation and the people who surround us, but ethically.

Using Tsleil-Waututh laws and cultural teachings, and as well as teaming up with world renowned scientists and researchers and anthropologists, marine biologists, we created a 1,200-page assessment on why the Trans Mountain [Pipeline] shouldn’t be built and shouldn’t come through our territory.

We found that this negatively affects our way of being, and all of those around us, and all of those who don’t have a voice: the land and the water, the animals, the orca whales, especially, and the fish.

It started with TMX, but it’s a good framework for people moving forward in any way in any industry coming in. These are the things we have to consider.

Can you explain some differences directly related to Sacred Trust that illustrate the differences between Indigenous governance and colonial governance?

Colonial law, “Crown Land,” those [concepts] are morally incorrect. They don’t really make sense. It’s a colonial occupying force. It doesn’t have validity to us. At the end of the day, of course, we abide by it, because there’s pretty violent repercussions [if we don’t].

That’s the cool part about being on unceded territory, there were no agreements made. All of the laws here [are] not valid.

Tsleil-Waututh law is the law we abide by, and I invite all others to abide by it. It’s sacred law and it obeys natural law. A lot of our laws happen to be very feminist, very equitable, and very sustainable. Sustainability and lifting up women and lifting up all people as equals just happens to be a really big part of it. I feel like it does benefit all people, and all people in existence now and all people who will be in existence in the future.

I really invite people to look at these laws and start considering them.

These sacred laws have been here since time immemorial, since the Tsleil-Waututh people were created on this inlet.

I understand that you moved here from your Tulalip territory to learn the Squamish language. Is that adjacent to the Tsleil-Waututh (Halkomelem) language? Why is language reclamation important to you?

Language reclamation is extremely important to me. When I was young, my parents tried to teach me as much as they could about language and culture. I was raised in my cultural ways, I was raised in my Coast Salish and adopted Plains ways. A lot of those ceremonies my dad goes to. That’s all I knew and all I know, but as far as language, that was something that was taken away from both of their parents.

My grandmother’s first language is Squamish, but in residential school that was beaten out of her. She said it is almost traumatizing to try and re-learn it sometimes. It was told to her that it was “the devils way,” so she would only say phrases.

When I was reading about how the language was almost gone — that was my grandma’s first language, it really broke my heart. I was like “This isn’t fair,” and I took time out of university to learn it. I thought, “This has to happen now before a lot of the first language speakers are gone. This is an endangered language.”

In Squamish, when you ask someone how they’re doing, you really answer. In English, it’s like “How are you?” and you respond “fine, good, okay…” but you don’t go into detail. But there, it’s really like “How are you?”

It’s a culture around caring and feeling and emotions are really welcomed. At any point, if you need to say something about how you’re feeling, that’s okay.

As far as learning Squamish instead of Halkomelem, I really wanted to learn Halkomelem my whole life, but Squamish is my grandma’s first language, so I wanted to honour that, and I have Squamish ancestry as well. There are significantly less speakers of Halkomelem. Squamish is what was available to me, but I would really like to learn Halkomelem.

My Ta7a says “English is from the mind; our language is from the heart.”

From my mom’s tribe, I learned Lushootseed.

Traditionally, how do matriarchs serve Indigenous communities and their families? What makes a matriarch?

The matriarchs have really important roles. What typically makes a matriarch is the oldest grandmother because she has the most knowledge. We have a really high respect for elders, especially the oldest. There are different ways of defining it, it’s not always the case, it’s somebody who carries a lot of teachings with them, and who carry a lot of traditions and knowledge as well and carry themselves extremely high. That’s also a matriarch: somebody that passes on knowledge. That’s a big part of the duty of the matriarch, they pass down the knowledge and the decisions and the ceremonies, they teach the community, and they carry the traditions. Someone who carries traditions is a big part of being a matriarch.

Do you consider yourself a matriarch?

I suppose I consider myself a matriarch-in-training. That’s an interesting thing to me. I would say so because the matriarchs learn from the ones before them, and I feel I carry a lot of my Ta7a’s teachings. Many of my older cousins are matriarchs-in-training as well. We are all carrying those teachings forward and we’re all learning how to be leaders, and a lot of us are leaders.

I’ll let other people say whether they want to call me that or not.

What makes you feel empowered as a matriarch?

I’m really young. I’m 22. We have such a high respect for our elders. Elders speak first, you always have to make sure they are taken care of. For me, it’s putting that aside and knowing that I’m strong enough on my own, despite my age, and it’s when my uncles and aunties lift me up and tell me I have a voice. Acknowledging that and acknowledging my own power, and my own validity. I have just as much of a right to speak as anyone else.

I understand you are working on a project about Tsleil-Waututh creation stories, can you tell me one?

Many, many generations ago, at the beginning of time, our first grandfather was walking along the shores of the inlet. He saw that all the whales and the birds and creatures had a partner in life, and he prayed to the Creator and asked, “Why do I have to walk this earth alone? Why am I alone here?” and suddenly he had this urge to dive deep into the inlet and grab two handfuls of sediment. He did and came back up to the surface and put them on the beach on boughs of cedar. He fell asleep next to it in the hot sun, and when he woke up, he saw a beautiful woman next to him, and that was our first Tsleil-Waututh grandmother. So, she is literally the inlet. She is part of it. That’s why we hold the inlet so close, we hold it up so highly and it is so sacred to us.This is something we all hold equally.

My dad says, “When you go in the water, you feel her love, the same way you feel your grandmother’s love.” That is so true for me: the ocean and the water are the most healing places. Here especially, but anywhere I go in the world, when I go swimming, I feel loved, and I feel healthy. That’s something that’s really sacred to us, and it’s healing. That’s home. It runs through our veins. Taking that forward, it’s something I want to honour, when I’m making this short film we’re working on.