Illustration by Susana Gómez Báez.

By Tayvie Van Eeuwen

@tayvieeee

We talk about the big things–residential school, the Sixties Scoop, missing and murdered Indigenous women, and contaminated water on reserves. However, we rarely examine the smaller marks of colonialism that infiltrate Indigenous daily life.

While Canada no longer operates residential schools, with the last facility closing in 1996, cultural genocide continues to be a reality. It’s present in how our nation educates our youth. How Vancouver talks about Indigenous folks in the Downtown Eastside. How we talk to our peers. Our families. Ourselves.

In my own family, this has taken painstaking forms–aiming to separate the Indigenous from the person. My whole life I’ve wondered where my mother and I fit, if anyone else was stuck in a cultural dichotomy. If Indigenous people aren’t supposed to share their ancestry, how do they find healing in shared experiences? This is where my research began.

There are approximately 1.4 million people in Canada who claim Indigenous ancestry, making up 4.9 per cent of the population. Proportionally, youth and children make up the majority of the Indigenous population, hinting that Millennials and Generation Z are feeling the pressure of cultural dichotomy in a big and real way. They make up the majority.

What does this mean for cultural identity, integrity, and connection? Those who make up the majority of Canada’s Indigenous population are the survivors or children of late residential school, child welfare, and the Sixties Scoop. They have lived in the fire of trauma.

As Charla Huber, a Sixties Scoop survivor, recounts in “Every Indigenous Person is Indigenous Enough,” these survivors and their children face unique challenges.

“‘Am I Indigenous enough?’ is common among urban Indigenous people,” Huber explains. “I have come to terms with the fact that I wasn’t raised with culture due to colonization, and the more I question my relevance the more I begin to understand that my experience and others’ similar ones are all unfortunately very Indigenous experiences in our country.”

Her sentiments aren’t alone. In fact, many Indigenous people are facing the same silent struggle, asking themselves, “Where do I fit?”

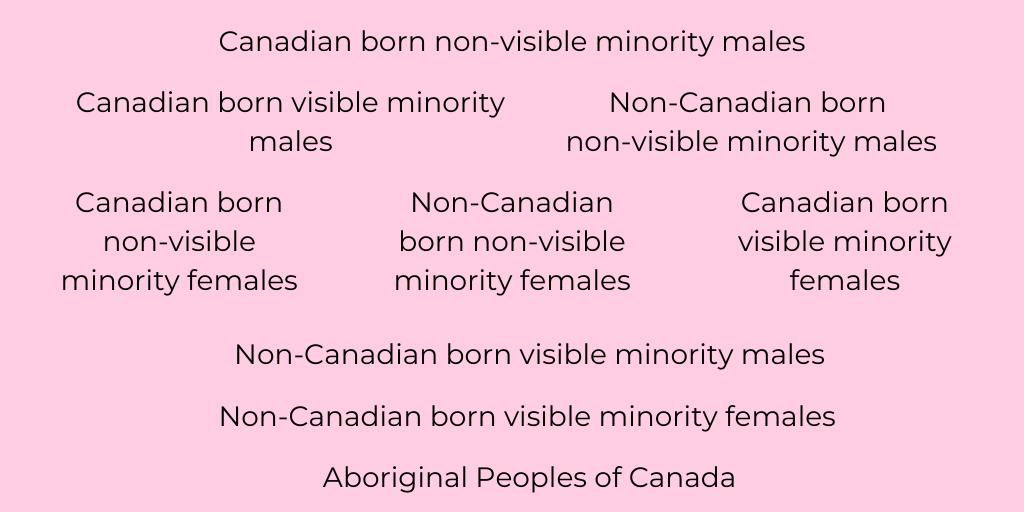

The current struggle of Indigenous peoples is tied not to just systemic structures, but social hierarchy, both of which are represented in the vertical mosaic–a term used by John Porter to illustrate Canada’s mosaic of unique ethnic groups that are unequal in status and power.

In 1965, Porter, a Canadian sociologist, published an academic book explaining the stratification of various groups within Canada. At the time, the mosaic only included a person’s ethnicity and their external appearance compared to the charter groups of Canada–those who colonized and had taken possession. Below all other ethnic communities, the Indigenous peoples of Canada were most disadvantaged.

Despite the latest vertical mosaic, including gender and homeland as factors, Aboriginal folks have not seen any change in their status within social and systemic hierarchies. So, what has changed?

Today’s vertical mosaic, in many ways, represents Canada’s social state, however, it fails to explain the impossible situation of categorizing “unusual” Indigenous folks. I noticed this while researching sociology concepts and realized the mosaic only takes into account outward appearance. Therefore, it simply cannot categorize all Indigenous peoples, especially those who are white passing or do not fit the textbook “Indian” look.

Canada has taught our society to look at Indigenous people in one form: dark skinned, braided hair, rugged, in a ceremonial outfit, and living in a rural area. This sole textbook image is damaging, placing Indigenous folks today in the position of internal and external judgement of not being “Indian” enough.

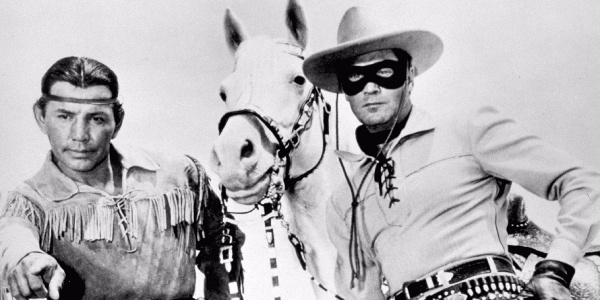

For Indigenous author Thomas King, this became the focus of one of his most prized works, “I’m Not the Indian You Had in Mind.” The poem, aimed at disarming media representations of the Lone Ranger and other typical stereotypes, is a powerful depiction of these challenges.

At Toronto’s Ryerson University, Indigenous academic support advisor Amanda Thompson explains this view is harming youth.

“The classic stereotypes that people associate with Indigenous people, whether they’re based on appearance or overarching character traits, impact how indigenous people view themselves,” Thompson told Ryersonian.“While it may already be difficult for Indigenous students to accept their identities, the issue is only compounded when they’re met with certain expectations of how they should look or act.”

Millennials and Generation Z are at the forefront of these issues, with many of their family members hiding their heritage to protect them. In some cases, parents took on a different ethnic cloak to shield their children from prejudice. Take, for example, Alita Tocher, from Tsilhqot’in Nation, who was told her background was Spanish.

Similarly, James Lee Morin, a young Métis woman, was shocked to find out about her Indigenous ancestry when she was 12 years old. In her father’s perspective, having lived with an inferiority complex, it was the right call.

“He said, ‘In my day, it was shameful to have that ancestry, you didn’t want to be known as the Indian,’” Morin explained to Ryersonian.

To tell her friends about her heritage took even longer. Explaining, “I didn’t want to tell anyone at school because I knew that they would just laugh at me and say ‘Well you don’t have a feather in your hair or any of those stereotypes that we’ve been learning in school.’”

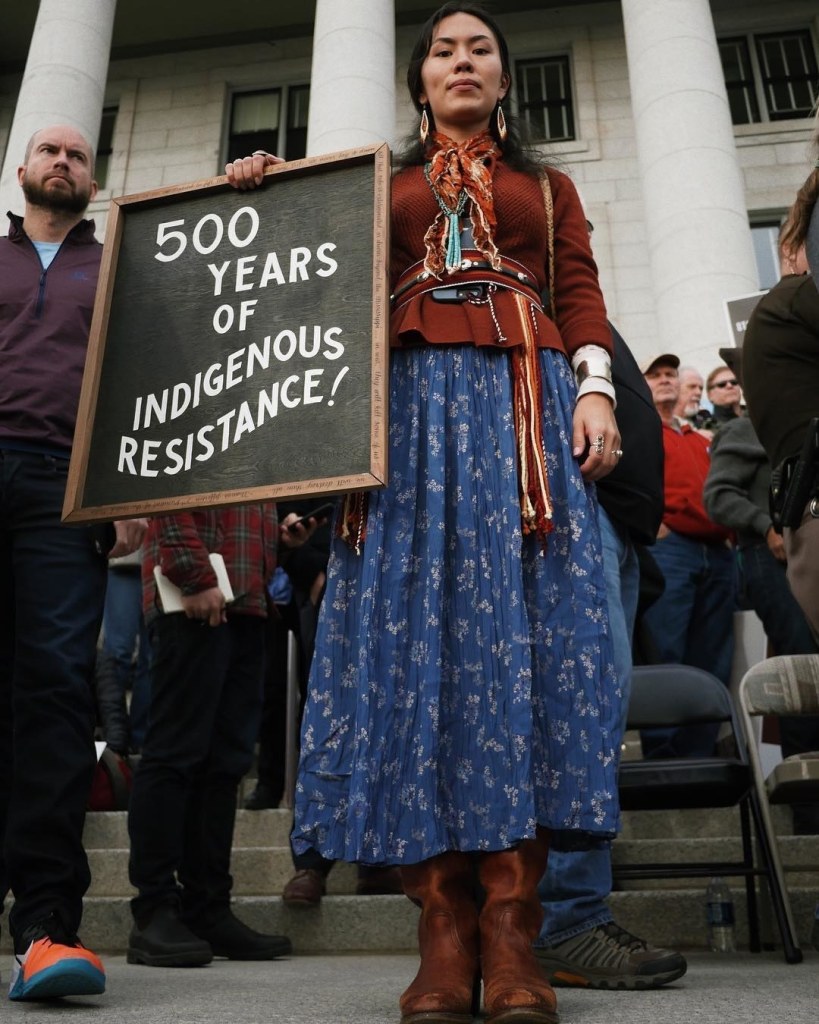

In all accounts, Indigenous youth and millennials recount the same thing: shame. However, many also began an exploration, as have I, to transform shame into solidarity. While some reserve residents are viewed as “too Native” and urban folks being seen as not Indigenous enough, colonialism affects the identity of all Indigenous folks. White passing people, however, experience a level of privilege not afforded to people of colour.

As Devan Cronshaw of “Every Indigenous Person is Indigenous Enough” explains: “There is no one way to be Indigenous. That was the plan with colonization all along. They wanted Indigenous people to feel disconnected. It’s not a mistake people feel this way.”

The start of social and judicial change is coming, although federal and global attitudes being still far behind. In Canada, Daniel’s Decision of 2016 helped to ratify Métis and Non-Status Indians in law, with a legal duty to include them in all Indigenous matters. Similarly, Delgamuukw v British Columbia provided precedent for Aboriginal communities to be consulted on land development. The case also helped to establish the judicial credibility of Indigenous oral history.

Locally, BC has voted to formally implement the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, making the province the first jurisdiction to do so.

While the battle for equality is not over, the concepts of what an Indigenous person looks, acts, and speaks like is broadening. Many Indigenous communities hold onto their history in the face of injustice. This, we will continue to do.

*This piece has been edited to better reflect non-colonial language.

Tayvie is a Métis/Anihšināpē and Irish/Scottish student and writer. Her circle is small, but her joy is large. She splits her time between over-thinking and visiting Disneyland. Read her articles to take a peek inside the world of mental illness and happy news, because it’s all about balance, right?