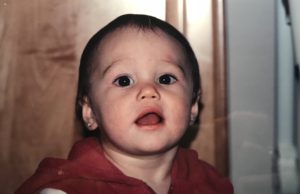

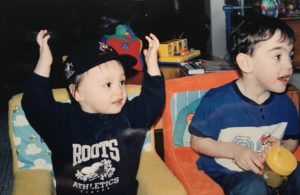

My favourite picture of my brother and I as kids

Most people have no recollection of memories before the ages of three to five. I’ve heard others say time and time again that they wish they were able to tap into that hidden vault of experiences. But for me, I’m grateful that I can’t.

My brother was born 10 weeks premature. After a traumatic delivery, he began to have Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC); a condition where the bowels of a premature baby blow out and cause the body to become septic. After many bowel surgeries to repair the damage, he developed cirrhosis of the liver caused by the food and nutrients given to him intravenously. He went into life-threatening liver failure and was sent to London, Ontario for a liver transplant, where my mom was assessed as a donor. At eight-months-old, he had the transplant. A few years later is where our story picks up.

When I was a toddler I flew out to London, Ontario, to visit my brother, Matt, in the hospital following a series of additional lifesaving surgeries. My mom had been gone for two months and I was yearning for the maternal comfort no one at home was able to provide. I had been living off of instant noodles and quick goodbyes as I was dropped off to my grandparents so my dad could work. I thought this was normal.

I have fragments of memories of that trip: sitting at the table with a bowl of ramen, seeing my brother being brought outside in a wheelchair, running to my grandma’s arms. Fragments are fine. But I’m happy I don’t remember a particular story my mom recounts from time to time. Frequently, the story accompanies teary eyes and a heavy heart on my mom’s part. For me, an out-of-body experience.

My younger self was having a severe mental breakdown. It was the end of my trip to London, Ontario, and I was laying on airport carpet in hysterics, unable to stop crying and screaming. My mom tells me she had to watch the ordeal on the opposite side of a glass wall while her child was being torn from her again. Apparently, my dad had to scoop me up and I didn’t stop crying for the next seven hours. How could you calm down a child who just had to leave her mom and had seen her brother on the brink of death? I still wouldn’t know. There’s no rationality when your family is in shreds.

The next decade of my life is an unusual story to the general public, but for anyone with medical issues, it’s hauntingly understandable.

If you were to walk into my house, it seems like a typical family home. But what I see are remnants of a life I’ve done my best to heal from.

Black and white photos to hide the yellowed skin from liver failure, cupboards full of medicine bottles, and bells that sit on every external door. Our walls purposely leave out certain aspects of our past and our doors ring on exiting, to protect me from leaving.

I didn’t even live at my house much of the time. I shifted between my room at my grandparent’s, the hospital, and my parent’s house. A few years ago my grandma moved out of her house, and I struggled with leaving my childhood bedroom behind. I have pieces of it now: the vintage desk I would draw my brother pictures on, the doll I snuggled while I slept, and the last jar of paint I ever used at her house. I keep them with me to remind me of my safe haven as a child.

The hospital was another home to me. To this day, the hallways of BC Children’s are second nature to navigate and some of the nurses and doctors still know who I am. My mom would sleep on two chairs pushed together, or a cot if she was lucky. I’d sit on the bed and play checkers with my brother and perhaps watch a show for a bit. A routine.

In succeeding years, I began to experience night terrors. A simple way to describe this sleep disorder is that it causes a fear reaction when a child wakes up. Everytime my brother left for the hospital, or was sick, I would have one. I would tried to leave the house, or hide under furniture while in distress. It took several years for my family to link his illness with my night terrors. To this day, they still haven’t taken off the bells.

I got used to being called down to the school office only to find out Matt was in the hospital again. Or, as I got older, seeing my mom’s name pop up on my phone in the middle of class meant that I should expect much the same.

I learned to be mature beyond my years before I was 10. I could run my household efficiently and knew how to be the adult when my parents couldn’t. I taught myself how to shut off my emotions for survival. In retrospect, the effects of my brother’s illness didn’t catch up with me until I was a teenager.

For perspective, the complexities of my childhood took on more than one face. My brother’s medical issues had ripple effects on the rest of my family, especially my mom who quite literally gave him part of her body. When I was around 10, my dad completely left the picture after a decade-long, tumultuous relationship. We had a lot to heal from.

When I started grade eight, the emotions of my childhood hit me all at once. One night, my mom found me on the bathroom floor in tears; I couldn’t physically get up. I went to the doctor who referred me for counselling, which I still go to weekly.

My family had been the cover story of newspapers for years, always being labeled an “inspiration” or “heartwarming recovery.” Underneath articles about our life, there was immense pain and leftover panic. How do you not fear the future when the past was strictly life or death?

Today, after 19 years of life and nearly 40 surgeries, my brother is, in all-outward aspects, thriving. He has spent years playing competitive sports and doing more than most people could dream of. Unless you saw the scars that cover his stomach, you wouldn’t know what he has endured. He advocates for those who have had or are undergoing transplants and has a passion for life that I wholeheartedly admire.

I guess the big question to all this is: how has my health been affected by your brother’s illness? The answer is: a lot. Physically, my immune system was never built up because our house became a sterile, “no sick people” environment. I didn’t go out if people were ill and I didn’t dare compromise my brother’s health. Now, I get sick six to eight times a year.

My mental health has been a pill that’s hard to swallow. Admitting you need help really is the first step to recovery and I resisted it with every ounce of strength I had until I burned out.

When you’re faced with death, abuse, and the fine line of your own willingness to live, you change. Above all else, I’m really fucking grateful that my brother is alive. I’m grateful my mom helps other kids through the Children’s Organ Transplant Society. I’m grateful to my sister who has been my everything and my step-dad for choosing to walk into our messy life, and messy past, and to my grandma, for being my second mom, you raised me good.

Most importantly, I’m grateful to myself. Our bodies keep us alive and do all the work when we lack the willpower to keep going. We judge and ridicule our bodies so much that we forget to thank ourselves; this essay, amongst a discussion on many things, is a formal apology to myself. My body loves me so much, it takes all the mental and physical pain I’ve been fed and continues to live, and thrive, and dance.

Thank you.