By Claire Matthews

@ce_matthews

Breasts, boobs, cans, knockers, bazookas, tits: call them what you want, but about half of us have them. Admittedly, I had to do a Google search of “euphemisms for breasts” and was surprised by how colourful some of the nicknames were and also how violent. Breasts exist in this sort of duality, not only because they usually come in a pair: you love ‘em or hate ‘em, see them as weapons or non-threatening, have them or don’t.

Thanks to the male gaze, women still wonder how much to show, when to show, and are they showing? Breasts seem to come with so many contexts they’re no longer just flesh.

Boobs: Women Exploring What it Means to Have Breasts, edited by Ruth Daniell and published by Caitlin Press, explores the multitude of experiences in having breasts.

Because of this still persistent patriarchal world we live in, I want to hear marginalized voices, specifically those who identify as women.

I want to hear my voice echoed back to me to know I’m not alone, to know we’re no longer silenced.

As much as Boobs is an anthology about breasts rather literally, it also feels like it’s a collection of voices from survivors—those who have suffered abuse, dysphoria, body shaming, and cancer. Sometimes celebratory, other times cathartic.

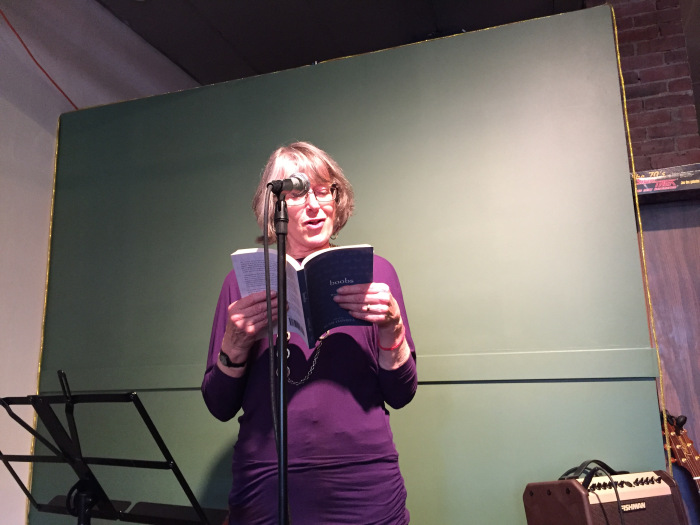

Loose Lips went to the Vancouver launch of Boobs at Heartwood Café and listened to the diversity of readers, from Emily Wight’s hilarious piece “Celebrate Your Curves with Free Shipping” to Maggie Wojtarowicz’s moving performance.

Boobs makes a clear commitment to representing the diversity amongst those of us who identify as women, including powerful stories of transitioning from both sides of the binary like Devin Casey’s “Skin Deep” and Sadie Johansen’s “The Balloon Stuffer.” The collection offers memoirs, essays, and poems from mothers, survivors of cancer and abuse, and a military veteran to name a few.

Editor Ruth Daniell was generous enough to answer a few questions we had about Boobs and some of the topics the anthology covers in a broader context.

Q&A with Ruth

The subtitle of Boobs is “Women Explore What It Means to Have Breasts.” What do you think it means to have breasts?

It means a million things, different things depending on who you are. But I think that, perhaps, one of the most striking things about breasts is that they mean that you are visible. Unlike penises and vulvas, which remain relatively inconspicuous under our clothing, breasts are visible—baggy shirts will only hide so much—which can be a good thing or a bad thing or, more often than not, it can be a mixture of both. To have breasts means to have some of your identity presumed by others. Sometimes that will be a handy shortcut but other times it will be harmful. To have breasts means that you have one more thing (well, two more things) to worry about as you negotiate yourself through our world.

Oh dear. That makes it sound like breasts are only a burden, but of course having breasts can be enormously fun, too.

What do you hope readers take away from the book?

My hope for readers is that [they] will feel less alone. I hope readers take away the message that they should be kinder not just to each other, but to themselves. More specifically, I hope that readers will take with them the knowledge that other people—from all different walks of life—also have complex problems and (sometimes) solutions to complex feelings about their bodies. I hope readers will appreciate that it is a hard thing to live in your body, and sometimes it is really sad but that it can also be joyful and sometimes really, really funny.

What was the most surprising piece you read during the project?

I’m not sure I can answer that fairly—each of the pieces in the book surprised and moved me in different ways. In general, I was surprised and grateful, over and over again, for the strength of these individuals that showed itself in their stories and poems.

One of my favourite sentences is in “Mirror Mirror on the Wall” by Heidi Grogan, a story about a cancer survivor and her nipple reconstruction surgery. Grogan describes lying down on the paper-covered hospital bed, then looking down and realizing that there is a hole in her sock: “I can’t look like a dork; I’m getting new nipples.” I just love that—that honest, ordinary, mundane anxiety within the “greater moment.”

The absurdity that that “greater moment,” that special occasion, was the occasion of getting new nipples. It was too absurd not to be true. It is very funny but also very moving, too, in context with the rest of Grogan’s story, in which she struggles with the decision to get breast reconstructive surgery in the first place. She asks herself, and the reader, what the functions of breasts are. If they are not producing milk, are breasts just for beauty? Is that enough? Are they superfluous? Are they worth replacing?

These kinds of questions—moral questions about beauty and functionality—surprised me each time they came up, and they came up again and again, often in the guise of ordinary observations, like noticing worn socks or chatting with a co-worker or watching TV alone at night or eating supper.

Devin Casey writes about getting top surgery: “I still sit too far away from the dinner table sometimes because I forget that I can sit closer.” That simple observation—a reminder that how we live in our bodies can change how we live in our world in so many ways, both big and small—surprised and moved me.

In your introduction you say, “Perhaps your boobs have disappointed you in some way.” It struck me how insightful this was and made me think of the expectations women sometimes put on their bodies, even seeing their bodies in pieces rather than whole. Can you give any further insight on why you think this is?

I’m not more qualified to guess at this than anyone else with breasts, or without, but I think it’s one of those “chicken or the egg?” scenarios. We put expectations on our bodies because it is through our bodies that we experience pleasure and pain and can inflict pleasure or pain on others. We put expectations on our bodies because other people put expectations on our bodies. We put expectations on our bodies because we feel like there are expectations to put expectations on our bodies. Is that too meta? I feel like our relationships to our bodies are complex, and cyclical.

We can educate ourselves about why we should be kinder to our bodies, and if we as individuals can learn to shrug off societal expectations about bodies and gender and sexuality—unlearn the harmful expectations—then perhaps, in turn, that will teach society to shift its expectations too.

Perhaps that answers your question from earlier. My hope for Boobs is that it can be a part of that education. My hope is that we can stop disappointing ourselves and start loving each other more.

Ruth Daniell is an award-winning writer originally from Prince George, BC, who currently lives and writes in Vancouver, where she teaches speech arts and writing at the Bolton Academy of Spoken Arts.

Join Ruth Daniell, the editor of Boobs: Women Explore What It Means to Have Breasts, along with contributing authors Francine Cunningham and Miranda Pearson, for a reading from the anthology this Wednesday, May 18, at Book Warehouse Main Street. Doors open at 6:30pm; reading begins at 7pm. Books will be available for sale and signing.

You can also see Ruth Daniell along with contributing authors Zuri Scrivens, Christina Myers, Lynn Easton, and Jane Eaton Hamilton for another celebration of Boobs on June 18th, at Trees Coffee on Granville Street.

Claire Matthews is a UBC MFA student, writer, editor, soap maker, and whiskey drinker.

Claire Matthews is a UBC MFA student, writer, editor, soap maker, and whiskey drinker.