By Michelle Cyca

@Michellecyca

The early aughts were a great time to be a teenage girl because TV was full of other teenage girls to look up to. Perhaps this is still true, but now I only watch TV shows about murder investigations, crime syndicates, and sad British people, and as far as I know those are the only categories left. But back then, abundant female protagonists—Buffy, Felicity, the sisters of Charmed— reigned over primetime.

My favourite heroine of this Noxema commercial-ready cohort was Rory Gilmore, of Gilmore Girls. Gilmore Girls features fast dialogue, low-stakes family drama, and cute boys. It has a bland, wholesome quality; despite the fact that it’s set just outside of Hartford, one of the poorest cities in America. The fictional town of Stars Hollow in which Gilmore Girls takes place has no poverty or crime, only an abundance of festivals and a small population of odd balls. While other teen-focused shows tackled date rape, death, and trauma, Gilmore Girls plotted an entire season around which Ivy League university Rory will attend.

This soothing, saccharine vibe may explain why Gilmore Girls persisted in my life as a comfort entertainment. Long after the show ended its run in 2007, I returned to it regularly, sinking into the screwball dialogue like a warm bath. But, eventually, I started noticing that it didn’t feel very good anymore. The water had gone cold.

What is impossible to ignore, from my adult perspective, is how little substance there is to the characters I loved as a teenager. Ultimately, this is a show about an affluent white girl from a wealthy, upper-class family who wants to go to Harvard. Rory goes to a fancy private prep school, paid for by her rich grandparents, who later pay for Yale. Rory’s goodness and moral virtue are mainly conveyed through her Disney-princess looks and her avid reading habits. As Paris explains: “People think you’re nice. You’re quiet, you say excuse me, you look like little birds help you get dressed in the morning.”

A recurring “joke” in the show is that Rory and her mother Lorelei eat a lot of junk food despite being thin. Long before the infamous Gone Girl monologue about “cool girls,” the show leaned into the idea that being able to eat a lot is an appealing personality trait, as long as you’re skinny. In contrast, Lorelei’s best friend Sookie (played by a criminally underused Melissa McCarthy, relegated to the role of bumbling sidekick) is a chef who is never seen eating at all; Rory’s private school frenemy Paris isn’t even allowed to have mac and cheese.

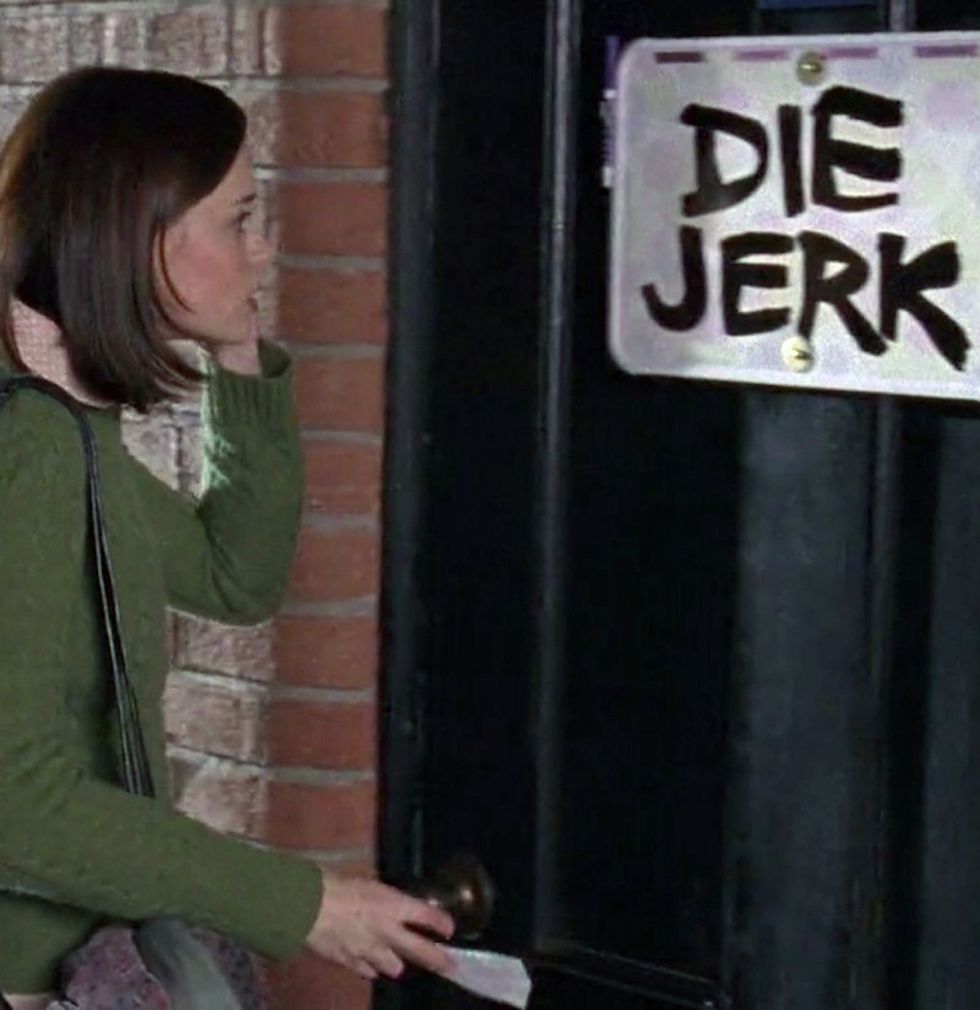

Beyond food, the treatment of all non-Gilmore characters on the show is relentlessly cruel. For a show about parents and children, it also takes a pretty dark view of motherhood. Sookie asks her husband to get a vasectomy after the birth of their second child, but ends the show unhappily pregnant again because he lied about getting one. This is treated as a goofy mishap, rather than a betrayal. Rory’s best friend Lane has the most tragic arc of all, dropping out of college, marrying her dumb-as-rocks boyfriend, and then getting pregnant with twins after her first disappointing sexual experience.

Gilmore Girls was the first show from Amy Sherman-Palladino, who began her career as a writer on another family dramedy, Roseanne. Since then she’s created three other series—the short-lived Bunheads, the even shorter-lived The Return of Jezebel James, and the critical darling The Marvelous Mrs Maisel— that share the same DNA as Gilmore Girls, with the same fast-talking, funny brunette archetype at the centre of the action. But despite the fact that all the protagonists are mothers (or surrogate mother figures), Sherman-Palladino’s depictions of parenthood are joyless. On Gilmore Girls, small children are unpleasant on the rare occasions that they appear: Rory’s half sister Gigi is a screaming monster who ruins Lorelei’s floors; Sookie’s son Davy refuses to turn off the TV during a dinner party.

The cast is very white, and the exceptions are uninspired. Lane is a first generation Korean-American, and her mother is portrayed as an overbearing Tiger Mom stereotype with a heavy accent (even though the actress who plays her, Emily Kuroda, was born in California). Lorelai’s coworker Michel, the only black character on the show, is a tokenized gay stereotype who never actually gets to have any romantic relationships. There were plenty of queer relationships on TV by the early 2000s, which makes the omission particularly bizarre.

Other people of colour appear, but usually only as maids in the Gilmore grandparents’ home, where they’re fired by Lorelei’s mother Emily for incompetence within one episode. This behaviour is lightly condemned and mined for humour—at one point Emily is sued by a maid, and Lorelei gives a deposition comparing her to Pol Pot— but the maids themselves are anonymous, interchangeable, just an opportunity to illustrate how unreasonable Emily is in comparison to Lorelai and Rory, who never stand up for them either.

The show reminds me of a t-shirt I owned in Grade 6 that proclaimed, in sparkly letters, GIRL POWER. As a child, I absorbed the message that a woman succeeding is somehow good for all women, regardless of whether those women use the same unearned advantages—money, nepotism, whiteness—that a small number of men have always relied on.

In that regard, Gilmore Girls is a useful antecedent for many of the pandering female-empowerment marketing messages that proliferate in our girl-boss era. Companies annoint themselves as feminist because they have female CEOs or target female customers or make products largely consumed by women. But scratch the surface and you find the same problems: no maternity leave, pay inequality, racism, ableism.

Recent exposes of start-ups founded and fronted by charismatic, beautiful white women—Audrey Gelman at The Wing and Ty Haney at Outdoor Voices—are the latest reminders that the success of a single woman does not, necessarily, lift up others. It is not revolutionary or empowering. It is just a pretty face on the same old inequalities.

Aspirational women are always marketed as self-made strivers, like Rory and Lorelai, with any advantages (family money, an Ivy League education, a wealthy husband) carefully obscured, as if they were unimportant details rather than the engines of their success. Rory’s accomplishments are treated as the hard-won results of her studious efforts, rather than the predictable path for a Yale Legacy from old money.

It’s possible to separate critiques of a character from those of a show. There are plenty of good shows about bad people, written with insight and awareness into the flaws of their characters: Succession, Breaking Bad, Mad Men, The Sopranos. But Gilmore Girls isn’t one of them. In 2002, it was enough to suggest a nice girl who loved books could be a role model. But in 2020, it’s just not enough.

Michelle Cyca is a writer, editor and content strategist. She lives on unceded Musqueam territory with her husband and baby, along with a very high-maintenance cat, and spends too much time on Twitter.