Dana Claxton’s work spans three decades, but in 2018—amid Canada’s thus-far disappointing attempt at reconciliation—the Hunkpapa Lakota (Sioux) artist’s work is more relevant than ever.

Dana Claxton: Fringing The Cube, the artist’s most recent exhibition housed at the Vancouver Art Gallery, offers a retrospective of her multi-media art through the years.

“This exhibit really shows the linkages of the themes in my work,” Claxton tells Loose Lips. “Today, we have seen the socio-political themes and the spiritual connections and then Indigenous aesthetics and being able to value those aesthetics.”

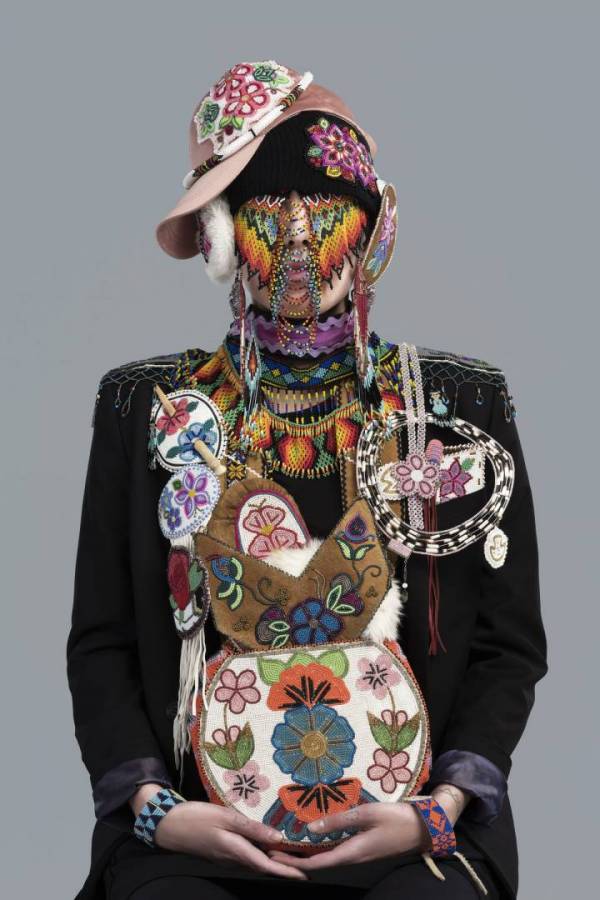

Thematically, all of Claxton’s work shares a similar vein: it’s a critique of colonialism and its effect on all of us, but it’s also a celebration of Indigenous beauty. The exhibit opens a top the Vancouver Art Gallery stairs with the “firebox,” (an LED Lightbox) featuring a woman in a beaded headdress, forging on in contemporary clothing, carrying her traditional crafts on the train of her hide cape—a veritable symbol for moving into the future while carrying the handiwork of your ancestors with you.

“Really, my intentions with these works was really about beautifying a liberation movement. People will have different experiences with this exhibit, however, and how they take that into the world outside of the gallery space is up to them,” she offers.

The exhibit takes the viewer into the artist’s earlier phases. Notably, Buffalo Bone China is a performance and mixed-media installation made from smashed English China sets. Originally composed from the crushed bones of plains buffalo—a massacre of the plains people’s economic independence—the China sets are smashed by Claxton herself (the viewer can watch this on one of the screens), denoting a rejection of English colonialism and the expressed anger that takes her there.

From anger, the crushed plates and cups are neatly arranged into circular piles, creating an homage to the buffalo themselves.

“I might be Indigenizing your experience,” Claxton reveals.

“If everybody is shedding their colonialism, and then re-Indigenzing, perhaps [that’s] a way of seeing Indigenous culture.”

Other installations include Indian Candy, a series of stereotypical images with a candy-coloured treatment such as the Lone Ranger’s Tonto and, again, a lone buffalo. Its neon-saccharine overlay serves as a comment, making these harmful images “easier to swallow,” while reclaiming the Indigenous narrative.

Later, the viewer moves into Claxton’s photography collections, including The Mustang Suite, a compelling (and feminist) take on a Sundancer, and more contemporary still, images of modern Indigenous men and their labour. Also included in the photography portion of the exhibit is what’s referred to by Grant Arnold (Audain Curator of BC Art at the Vancouver Art Gallery and curator of Dana Claxton: Fringing the Cube) as the red room: a collection of images that illustrate a haunting yet powerful narrative of family and femininity.

While Fringing The Cube doesn’t take a chronological or linear approach—echoed, of course, by circular shapes evident in all of her work—we land on the fireboxes portraying women in colourful beaded headdresses, showing off the handiwork of her culture, and ultimately, celebrating its beauty.

“As a sundancer, which is all about the ceremony, it’s all about the circle. The sun, the community in the circle, the four directions that create the circle, the circle of life: it’s a re-occuring theme.”

Dana Claxton: Fringing The Cube runs from October 27 to February 3 at the Vancouver Art Gallery.